The investment industry is riddled with short-hand approaches to analytical work.

A recent survey of professional investors found that market multiples were by far the most popular approach to valuation among nearly 2000 respondents. P/E multiples were used 88% of the time, followed by the EV/EBITDA ratio 77% of the time.

Using a multiple to calculate the intrinsic value of a company is not valuation, it is a shortcut. The only real way to value a cash-generating asset is to discount its future cash flows to the present day.

Using a P/E ratio as your primary valuation tool invites a host of analytical errors that increase the odds of negative outcomes.

Let’s quickly illustrate why a P/E ratio cannot dictate value. Since estimates of earnings per share are available, analysts must only choose a multiple to determine a company’s fair value and then compare the result to the current price and assess whether it is undervalued, overvalued, or fairly valued.

Since we already know last year’s earnings per share or next year’s consensus earnings per share estimate, we need only estimate the appropriate P/E. But since we have the denominator (earnings), the only unknown variable is the appropriate share price. To summarize: to estimate value, we require an estimate of value.

This flawed logic underscores the fundamental point: The P/E multiple does not determine value but rather comes from value.

“PE analysis is not just an analytical shortcut. It is an economic cul-de-sac.” - Michael Mauboussin

Accounting vagaries also make earnings a pretty redundant profit metric. Management has a great deal of discretion in determining the earnings they report to the market.

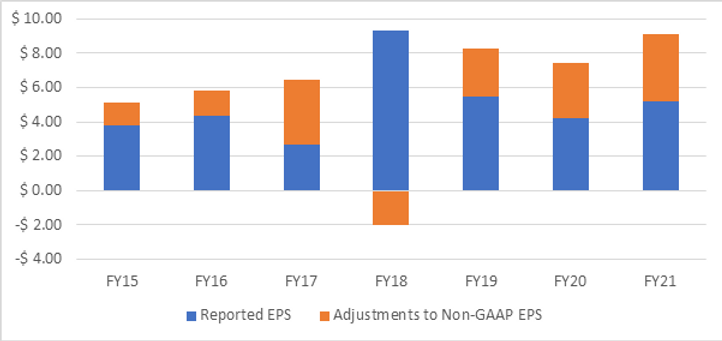

A common practice today is for management to report non-GAAP or “normalized” earnings alongside reported earnings. Management teams have significant discretion on what adjustments to make (restructuring costs, acquisition costs, impairments, currency translation losses) to reported earnings to get to their “real earnings”.

What is worse, non-GAAP earnings are what the market follows and what analysts attempt to forecast. The diagram below shows Stryker Corp’s reported earnings and the adjustments management make to get to non-GAAP figures. In certain years, adjustments almost equal half of the group’s annual reported earnings!

“Cash is a fact; profit is an opinion.” - Alfred Rappaport

We can look at certain economic concepts to help us conceptualize the P/E ratio and make it somewhat useful.

Merton Miller’s and Franco Modigliani’s (M&M) foundational paper on valuation demonstrates that the value of any firm is equal to its steady-state value plus future value creation.

Steady-state value (using the perpetuity method) can be defined as net operating profit after tax (NOPAT) divided by a company’s cost of capital, plus any non-operating assets such as cash and equivalents. Steady-state implies a firm has reached full maturity and any incremental investments will not add to or subtract from firm value. i.e., return on invested capital is equal to the cost of capital.

Future value creation is defined as returns on investment above the cost of capital during the competitively advantaged period.

Michael Mauboussin shows us that M&M's equation for firm value can be manipulated to consider multiple analyses. Specifically, a P/E multiple can be split into two parts – a portion for the steady-state value of a firm, and a portion for the value that will be created in the future.

The underlying value of a firm does not get impacted by growth when the firm is in a steady-state. A company can continue to grow earnings, but it will only earn its cost of capital on investments made. It lends $10 to make $10.

The steady-state value of the firm can be translated into a PE multiple. It would be the reciprocal of the cost of capital of the firm (remember, the inverse of the P/E is a company’s earnings yield).

If a company’s cost of capital is 8%, then its steady-state P/E (or commodity P/E) is 12.5x. If the company trades at a higher multiple than 12.5x, then the market assumes that the firm will generate returns on invested capital ahead of its cost of capital. If the firm is trading below 12.5x, the market is implying that the firm is destroying shareholder value.

The difference between a firm’s actual P/E multiple and its commodity P/E is what the market is ascribing to future value creation. Over time, as a firm’s competitive advantage period shortens due to competitors driving out excess returns, a firm’s P/E multiple should drift toward its commodity P/E.

It is common to hear from market participants that a company is a buy because it is trading well below its historical average P/E multiple. In many ways, this is a vague statement.

Unless the company’s prospects for returns on incremental invested capital and growth are consistent with its historical pattern, then there is zero evidence that it should trade in line with its historical average. In addition, a company’s multiple deserves to be lower or higher depending on the change in its cost of capital.

References

Jerald E. Pinto, Thomas R. Robinson, John D. Stowe, "Equity Valuation: A Survey of Professional Practice," Review of Financial Economics, Vol. 37, No. 2, April 2019, 219-233.

Michael J Mauboussin, Dan Callahan, “Everything is a DCF Model”, Morgan Stanley Consilient Observer, 3 August 2021.

Michael J Mauboussin, Alfred Rappaport, “Expectations Investing”, 2021.